Anatomy & Function

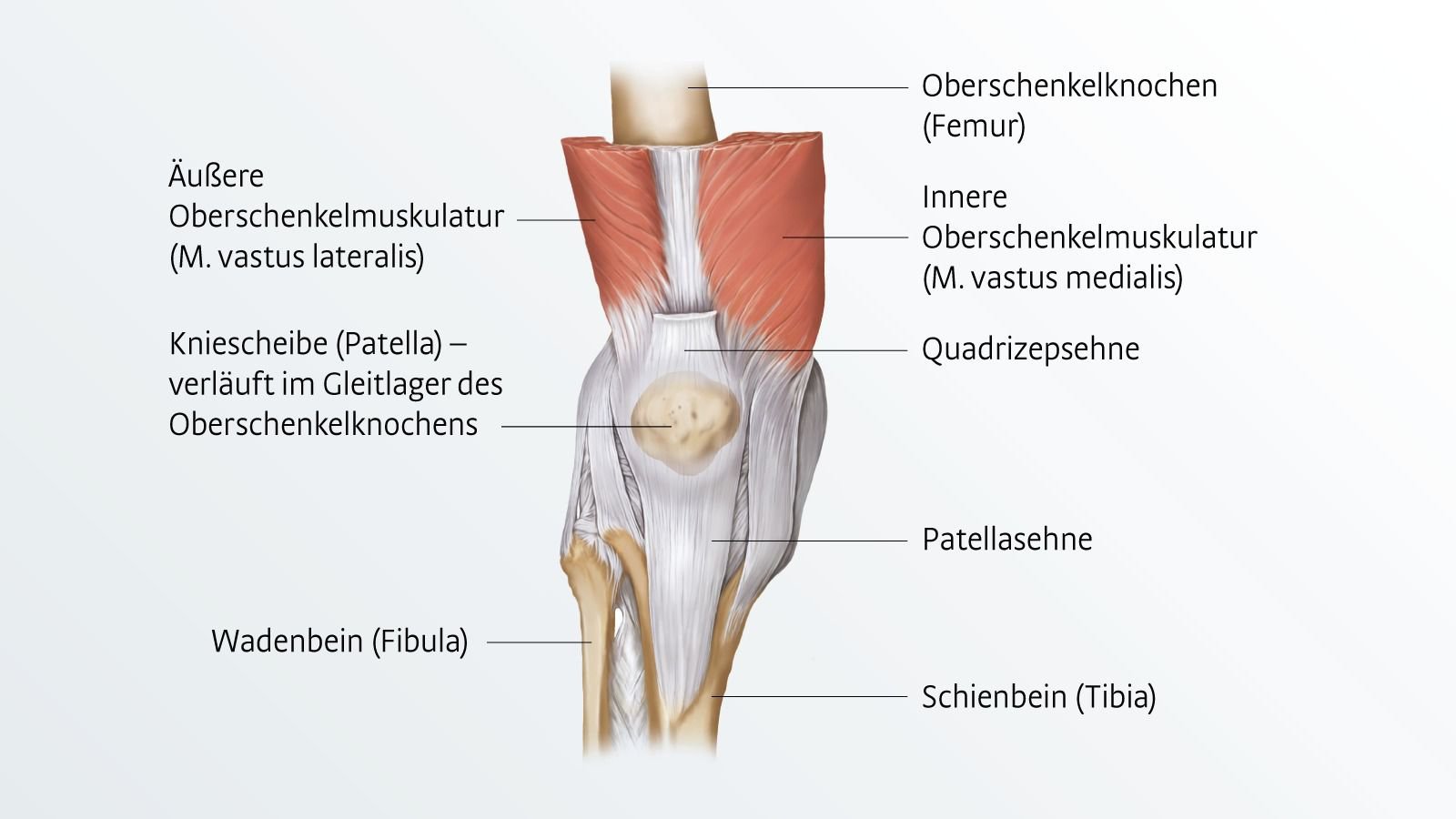

Patella is the Latin name for the kneecap. As a component of the knee, the small, flat, heart-shaped bone between the upper and lower leg protects the knee joint and facilitates its movements. Numerous complaints or pains in the knee can stem from the kneecap. The kneecap facilitates every movement in which the knee is bent or extended. As the attachment point for the tendon of the large thigh muscle (quadriceps, Musculus quadriceps femoris), it enables the problem-free transmission of force from the anterior thigh muscles via the patellar tendon (Ligamentum patellae) to the tibia. In addition, the patella improves the leverage and biomechanics of the tendon as a spacer between the tendon and the underlying bone.

Symptoms & Complaints

The kneecap is responsible for many knee problems. It is not always the bone itself that causes problems - the complaints often originate from the tendons or the cartilage on the back of the kneecap. Pain in the front of the knee is often referred to as patellofemoral pain syndrome (FPS).

Various factors can be considered as its trigger:

- Overload or incorrect load

- Muscle or ligament shortening

- Trauma or sports injury

- Malalignment or an incorrectly formed patella

- Benign or malignant neoplasm

- Complaints triggered by the spine, hip and leg axis misalignment.

As a result, the kneecap may hurt, jump, shift or become inflamed. The inflammation then also affects neighbouring areas such as the bursa or Hoffa fat body (bursitis praepatellaris, bursitis infrapatellaris, Hoffa-Kastert syndrome).

Causes

Wear and overload

Disease patterns in the area of the kneecap that are based on wear and tear or overloading are, for example:

- Chondropathy (chondromalacia patellae): mostly affects girls and young women, patellar cartilage becomes soft and wears away

- Patellar arthrosis (retropatellar arthrosis, cartilage degeneration): worn, worn cartilage

- Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome in children or patellar tendinopathy (jumper's knee) in adults: altered tendon tissue at the bone-tendon junction.

- Osgood-Schlatter's disease: Death of parts of the tibia bone at the attachment site of the patellar tendon

Malposition or maldevelopment

Possible malpositions or maldevelopments of the kneecap are:

- Congenital patellar dysplasia: malformation of the patella

- Patella alta: patella that is too high

- Patella bipartita or P. multipartita: Patella consists of two or more parts; the reason is disturbed bone formation (ossification disorder).

- Malalignment of the kneecap: bow or knock-knees (genu valgus, genu varus) or flat feet.

- Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFSS)

Accident and trauma

Accidents and trauma can cause various types of damage to the patella:

- Patellar contusion (knee contusion )

- Patellar fracture (patella fracture)

- Cartilage damage

- Patellar tendon rupture: partially with bony avulsion (possibly pre-damage of the tendon due to other disease)

- Patellar luxation: Patella jumps out of the joint (luxation) or shifts sideways (subluxation); also possible as a result of malalignment

Diagnosis

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFSS)

Patellofemoralpain syndrome (PFSS) is pain in the patellar gliding path between the thigh and the kneecap. Patients usually refer to this as pain next to, behind or below the kneecap. Therefore, it is often commonly referred to as "anterior knee pain". Complaints occur especially when climbing stairs, after sitting for long periods of time, or in connection with athletic activity. Young, athletically active women are particularly often affected. The most common causes include shortened or weakened thigh muscles, an incompletely developed patellar gliding groove, a leg axis deviation (e.g. knock knees or bow legs), reduced leg axis control and stability, or a tilting of the patella.

In a healthy state, the kneecap sits in the so-called sliding bearing of the thigh bone like in a guide groove and is additionally held in place by lateral ligaments. The muscles actively support the central sliding. Causes include malalignment of the leg axis (knock knees or bow legs, "squinting knee eyes"), tilting of the patella or an incompletely formed gliding groove. Weak muscular or neuromuscular activity can lead to the kneecap not being exactly centred in its gliding groove. The resulting anterior knee pain occurs mainly under load.

The pain is felt behind, next to or under the kneecap. Pain occurs especially after long periods of sitting or prolonged immobilisation of the knee joint (start-up pain), but also in connection with sporting activity or when climbing stairs. Young, athletically active women are particularly often affected.

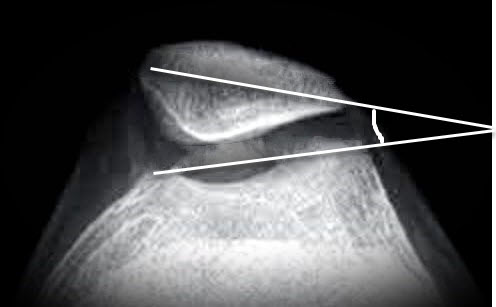

Lateral patellar shift: (patella tilt angle): α angle between patella and trochlea line (up to 5° normal)

Patellar instability

The causes of patellar instability are multifactorial. In addition to anatomical conditions (dysplasia of the sliding bearing, position of the leg axis, etc.), soft tissue-related changes (muscle weaknesses, dysbalances, etc.) play a major role. In addition to an accurate history, clinical examination, X-ray documentation and magnetic resonance imaging are the most important diagnostic tools. In the case of a first injury (patellar luxation without concomitant injuries), a conservative approach with immobilisation (approx. 3 weeks) and subsequent physiotherapy is possible.

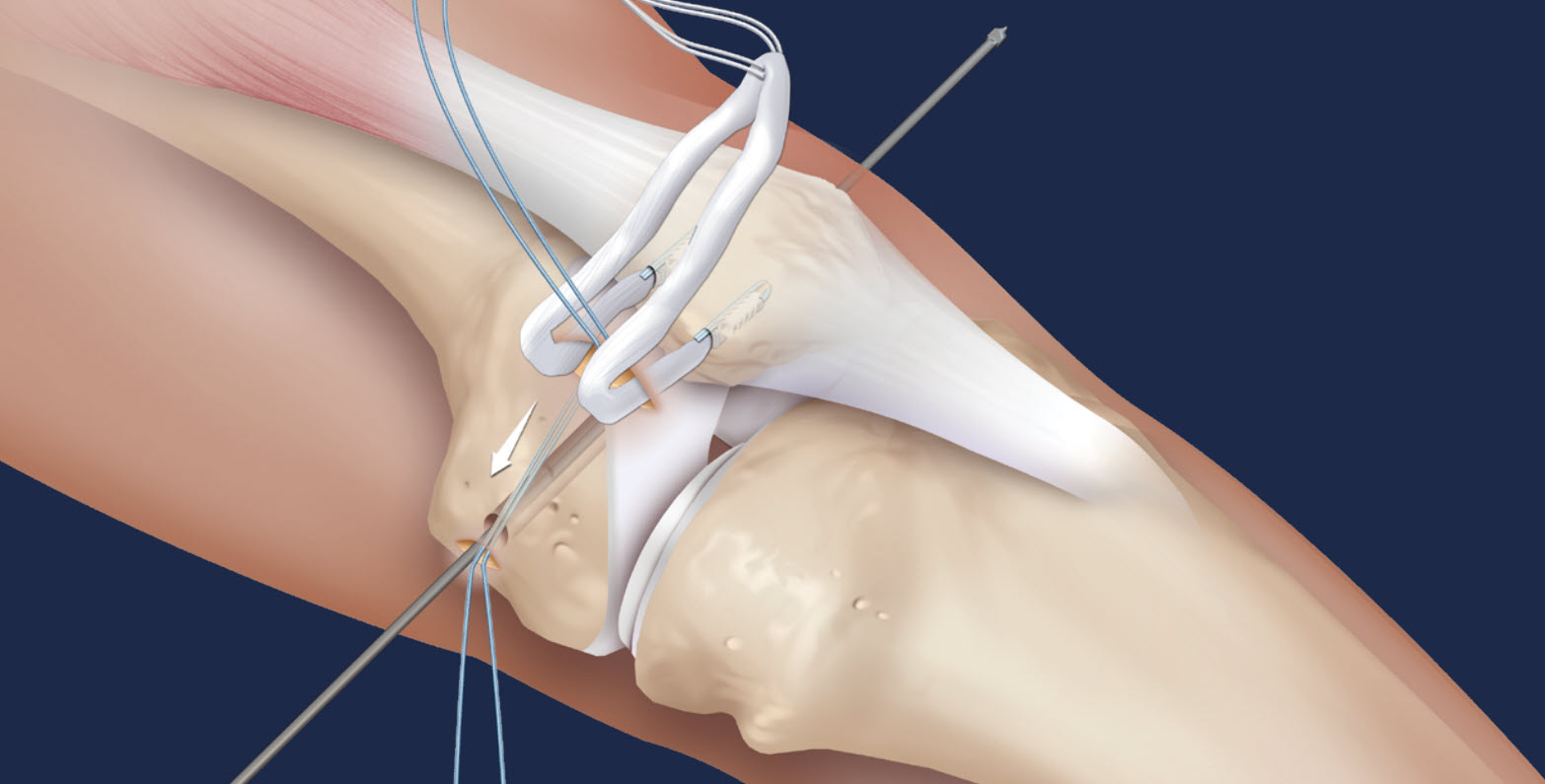

The medial patellofemoral complex, consisting of the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) and the medial patellotibial ligament, is the most important passive stabiliser of the patellofemoral joint. Since it has been shown that rupture of the MPFL is the main pathological consequence of patellar dislocation and biomechanical studies have shown that the MPFL, as the main passive stabiliser, counteracts patellofemoral instability (PFI) and lateral patellar dislocation, reconstruction of the MPFL is a commonly accepted technique for restoring patellofemoral stability. Therefore, numerous techniques for reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral complex have been described with promising clinical results. However, as it is well known that non-anatomical reconstruction of the MPFL can lead to non-physiological patellofemoral loads and movements, the aim of a reconstruction must be to achieve the best possible results.

movements, the goal of surgical intervention must be an anatomical reconstruction.

Indication for MPFL reconstruction (ligamentum patello-femorale)

As patellar instability mostly occurs in extension or slight flexion with minor trochlear dysplasia, it can usually be treated by MPFL reconstruction. After an acute patellar dislocation, the MPFL is almost always ruptured and, in the case of congenital trochlear dysplasia, additionally weakened because the patella has not been properly guided since early childhood. The additional stresses and strains on the medial soft tissue complex due to this misguidance can lead to an underdeveloped or insufficient MPFL and eventually to instability.

Treatment

If, as a result of the malpositioning of the kneecap, there is an increased amount of pressure on the lateral kneecap (patellar laterlisation), this can lead to cartilage wear with subsequent arthrosis in the kneecap joint. Severe knee pain at the front is the result.

Conservative therapy

In the case of lateralisation, treatment is usually conservative at first, i.e. without surgery.

- Bandages: To stabilise the kneecap and the knee joint, a knee bandage can be worn to improve the centring of the kneecap in the gliding groove.

- Physiotherapy: Exercises and regular independent training to strengthen the thigh muscles, stabilise the pelvic-hip region and leg axis training can alleviate the symptoms.

Operation

If the symptoms do not improve with conservative therapy, we have two surgical techniques at our disposal:

Lateral retinaculum splitting (lateral release)

In the case of a lateral (located in the outer patella area) hypercompression syndrome with an externally fixed patella, there is the option of arthroscopic or open lateral retinaculum splitting (lateral release). We perform the operation almost exclusively arthroscopically in the case of rather fixed, non-unstable patellae. This surgical technique has also proven successful in the context of anterior knee pain in patellar tendinopathy with or without structural damage to the patellar tendon. The aim of the procedure is to relieve pressure on the outside of the patella, especially in cases of cartilage damage to the lateral patellar facet, particularly in higher degrees of knee flexion. In the case of bony pull-outs, a patellar reduction (lateral facettectomy) can also be performed. In exceptional cases, the combination of a cartilage reconstructive intervention with a bony correction to create a better biomechanical situation is useful.

Lateral retinaculum lengthening

Lateral retinaculum lengthening is not an arthroscopic operation. It is preferably performed on rather unstable patellae, as an opening of the joint capsule is avoided. The lateral retinaculum is first exposed and the outer part of the retaining ligament is cut superficially to a length of about 3-4 cm at the outer edge of the patella and detached from the deep layers. The deep layer is then also incised and the resulting deep cut surface is then sutured back to the superficial cut surface. This lengthens the ligament and the patella repositions itself in the centre of the knee and can find its way into the gliding groove. Due to the reduced tension of the retaining ligament, the patella is no longer so tilted and the cartilage of the outer posterior surface of the patella experiences pressure relief, so that cartilage wear is reduced and, moreover, pain on the outside is significantly reduced.

Reconstruction of the patellofemoral ligament (MPFL)

The anatomical reconstruction of this ligament can heal recurrent patellar luxation. The surgical procedure provides for the removal of the body's own gracilis or semitendinosus tendon, which is then fixed to the inner lateral patella with 2 thread anchors and to the inner femur with a bioabsorbable screw, after previous arthroscopy, during which luxation-related damage to the knee joint, e.g. cartilage damage, can be repaired. Wearing a knee joint orthosis for 3-4 weeks, the ligament reconstructed in this way usually heals safely and completely and prevents future patella dislocations. The advantages of this method compared to conventional procedures such as "lateral release" or "medial ligament reconstruction" lie in the anatomically optimal reconstruction of the MPFL and thus a significant reduction in recurrences.

Aftercare

More information will follow shortly.

FAQs

More information will follow shortly.